Book Girl!

So, do you remember back in the fall when I asked...

Read MoreSo, do you remember back in the fall when I asked...

Read MoreCross-posted at the Rabbit Room. I’ve come to write today in a downtown coffee shop where books line the walls and the air hums with slow, jazzy music. I haven’t accomplished a single useful thing. Instead, I’ve cupped my coffee close, sipped it slow, and let my sleepy eyes roam over the rim of the mug. Mostly, I’ve spied on my neighbor. A scholarly air hovers about her along with heaps of textbooks, stacked notebooks, and four different kinds of pens. She’s working very hard; eyes down under her fringe of dark hair, pen at a swift scratch, earbuds wedged in tight against the lazy aura of this place.

But every so often she stops. With a distinct sigh, she reaches for her mocha and sets down her pen. And as she sips, she stares. For propped against the nearest pile of books is a vivid photo of Audrey Hepburn. The girl beside me fixes her eyes on that photo, never blinking as she takes a long sip of coffee and chocolate. Then she sets down her mug, wriggles up a little straighter in her seat and sets to work again. I cannot help my surreptitious stare. The strength she obviously takes from that photo fascinates me, as if in fixing her eyes upon it she receives some new shock of courage.

I turn reluctantly back to my own book-piled table and cappuccino. A blank computer screen and a blank notebook are open before me. I ignore them. I open the topmost book on my pile, a series of essays by the poet Denise Levertov. My good friend Ruth is my source for modern poetry and when she tells me to seek out a poet, I go for it as I trust both her taste and also her navigation of the current age of poetry (a sphere of which my knowledge is slight). When she quoted Levertov and I found this book the very next day, I bought it. I am only one paragraph in before I stop, eyes arrested by these words:

“I believe poets are . . . makers, craftsmen: it is given to the seer to see, but it is then his responsibility to communicate what he sees, that they who cannot see may see, since we are ‘members one of another.’”

I have studied many facets of the writer’s vocation, but this idea of Levertov’s startles and even stings me. She seems to class writing with spiritual imperatives like loving your neighbor and telling no lies. I squirm in my seat, abruptly uneasy in conscience. I think I do see as she describes—imperfectly and with wandering attention. The scenes and people that brim my imagination, the joy glimpsed like light on a far-off hilltop, the story worlds that come to my mind more as gift than anything else, these compel me to write. But I rarely share them. For every one essay or story I do show the world, a dozen more lurk behind my eyes and in forgotten computer files, unknown to a single other soul. I’ve never thought of sharing my writing as a duty; perhaps I’ve seen my best pieces, the ones I actually like, as glimpses of beauty I simply must pass on, but I’ve certainly never thought of that sharing as an imperative in the same class as adherence to the golden rule. I like the luxury of considering my inner world a private one to be shared only when, and if, I desire.

I sip more cappuccino and feel stung by Levertov’s words. The truth is that writing often terrifies me. Not the easy kind of freelance work and editing projects and countless small jobs. Those I can accomplish with mind alone, thankful to earn my bread, and grateful, I admit, to avoid those clamorous dreams that beg to be told. Because oh, I don’t know how to begin to set the best things forth. I half begin then draw back in fear. My imagination blazes with pictures begging to be written, but my words seem too frail to bear them. I’ve set down countless sentences, cast dozens of hours to typing away only to scrap the whole thing in sheer frustration. My pride cringes to admit that, but Levertov’s words add the sting of conscience to my discomfort. I tell myself I will get to them soon, that when I have quiet or rest I will finally tell that one story that glimmers and sings, unwritten in my mind. The truth? I’m afraid I cannot do that story justice. I doubt my skill. I doubt my vision; I wonder if the worlds I know within myself might be deemed just silly by a reader. I don’t want to be mocked. So the story stays locked in the little room of my head and fear is the bolt on its door.

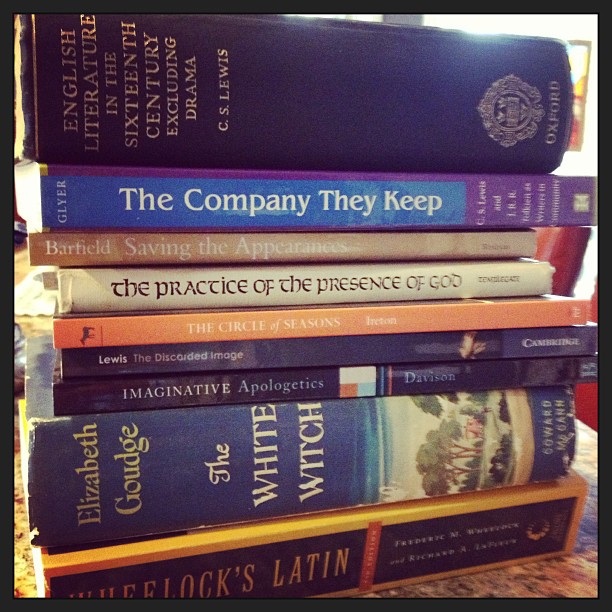

I glance again at the girl next to me to escape the discomfort now burning in my throat and I wonder. What does she “see,” what true vision does she touch through her contemplation of Audrey Hepburn? Did Audrey know she was embodying an ideal, and did she offer it willingly? I glance down at my own table, and my eyes wander to the pile of books I have toted with me. Again, my heart burns with conviction. For each of the books before me has been the sort of gift that Levertov describes, stories that allowed me to see, to taste, to grope my way forward when I felt blind. I would not have made several hard, defiant decisions this year without the vision provided to me by a few generous writers.

In my moments of crisis, when the landscape of my own mind and soul were fogged and dim with confusion, several writers kept me in hope. I opened their stories in the evenings, when my heart and mind were exhausted with the over-thinking required by major decisions. The worlds they had made and the people they presented were a refuge to me. Wendell Berry’s Port William. The Eliot family and their home of Damerosehay in Elizabeth Goudge’s Pilgrim’s Inn. The artistic grit of Thea in Willa Cather’s Song of the Lark. Nouwen’s story of God’s mercy traced through his contemplations on Rembrandt’s painting of the prodigal returned.

They sheltered me. When I was blinded by doubt, I journeyed on by the vibrant light of their created worlds. As I struggled toward wisdom, feeling homeless in soul as I teetered between several possible futures, those stories were my refuge. I was nourished by the power of what they presented as possible. I sheltered within their scenes, stood beside their characters, then stood back on my own two feet to reclaim my own vision and walk the long road required to bring it to life.

As I mull this, I pull out my journal and page back through my last months of notes, skimming the quotations I jotted down from those companion books. At one particularly long quotation, I stop, reading again a favorite passage from Song of the Lark. In it, the heroine Thea, like me, feels battered by the wide world in which she is fighting to establish her own vision of life. But Dvorak’s New World Symphony revives and steels her for the challenge. I read the scene again:

Something had got away from her; she could not remember how the violins came in after the horns, just there… A cloud of dust blew in her face and blinded her. There was some power abroad in the world bent upon taking away from her that feeling with which she had come out of the conference hall. Everything seemed to sweep down on her to tear it out from under her cape… Thea glared round her at the crowds, the ugly, sprawling streets, the long lines of lights, and she was not crying now… Very well; they should never have it. As long as she lived that ecstasy was going to be hers. She would live for it, work for it, die for it; but she was going to have it, time after time, height after height. She could hear the crash of the orchestra again, and she rose on the brasses. She would have it, what the trumpets were singing!

And just like the girl at the table next to me, I sit suddenly straighter in my seat. Here I am, reading about another person sheltered in trial by the vision offered by an artist. Dvorak’s music sheltered Thea (and no doubt Cather, Thea’s creator) when she doubted, renewed her strength to fight, to acknowledge the beauty she knew as the real thing over against the clamor of the world. I flip the page of my journal. There, in like manner are Nouwen’s words about Rembrandt’s painting of the prodigal son, telling how the color, line, and form so faithfully painted by one man ushered him into the arm’s of the Father’s mercy. Rembrandt’s vision sheltered Nouwen. And that encounter produced Nouwen’s book, whose vision now shelters me. And suddenly I am breathless.

Every work of art reaches out across the centuries, and each is a vision that casts a flame into the darkness. The wonder is that one great light wakes another. The song of one wakens the story of another. The story she told becomes the poem he made that kindled the painting in yet another’s hands. Each is a work of obedience. No artist can cast their flame of vision without a twinge of fear that it will simply fade or even pass unseen. But each is also a work of generosity, precious, private worlds offered in a self-forgetfulness that pushes aside vanity, insecurity, perfectionistic pride.

Levertov is right. The visions set forth in the books (and paintings and songs) we turn to for hope are offerings of love, given in the recognition that we truly are members of one another. We all bear the same hunger for eternity. We all walk forward in the dark of doubt, reaching for something we can’t quite name. We yearn to discover who we are meant to become, what it is we hunger to find in those midnight hours when our hearts will not be sated. But the artists and storytellers and makers of song offer the inner vision they have known as a sign of hope to the hungering world. They invite us into the sacred, inmost rooms of their minds and let us stand at the windows of their own imaginations where we glimpse, ah, wonders we might never have dreamed alone.

I glance again at the girl next to me. She is unrelentingly diligent. Who knows what she is writing, perhaps in response to the beauty she has seen? I brush my hand over the books whose weathered covers bear the scuff and dent of my many readings. The life within them crackles under my hand. I meet the stare of my own silent notebook, blank before me, and my pen sitting lonely on the page. I sigh and wriggle up a little straighter in my chair. I pick up that pen. At the very least I can write what I have just seen. A tiny gift, but a good place to begin.

I prove this quotation true at the start of just about every season. I simply cannot enter a fresh spate of months without a stack of doughty books to march down the road of those vast and undiscovered days beside me. I'm a happy woman today because I've found my companions. My summer list is set. Glory be.

This summer, I feel that I am walking with a faerie host. There is such richness in the books pictured below. I must admit, I always feel a little like one of those clever heroes in a folk tale who manages to win the favor (and the secrets) of some fantastic faerie personage. It is so vastly satisfying to hunt down and corral all the books I want to read, stack them high, and know that they will soon yield their comradeship and courage to my hungry mind. The hunt for the out-of-print books I want, the scouting of just the right titles, it feels like a contest and a game to me. A pile like this means I've won something rich.

Now, as soon as I posted this picture, I realized that I needed a bit more fiction and poetry. So I begged the advice of my friends and they fleshed out my list. The new books aren't pictured yet, but here are the suggested titles, for those who want to know. For fiction, The Trunk by Elizabeth Coatsworth, The Faraway Tree Stories by Enid Blyton, Descent into Hell by Charles Williams, The Invisible Bridge, Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh, and Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell. For poetry (I always go to my expert friend Ruth), I was pointed toward the Collected Poems by R.S. Thomas, and the poetry of A.E. Stallings.

And NOW, I want to know what's on your summer reading list. One, two, three... go!

I couldn't resist. I read this marvelous article and had to share it. Not only does the author quote most of my favorite writers, she writes about how words nourish and form us. Bless her!

A good Easter Monday to you, my friends. This blessed, rainy day finds Joy and me bundled in my little car Gypsy, rushing down the highway toward Asheville as the sun tussles with yet another storm. We don't mind the rain, in fact, it offers the spice of wildness to our travels. Brooding skies tinge a journey with mystery, while a cup of coffee is good as a faerie's brew to kindle courage in the bones. We have both.

As a last savor of Easter this stormy morn, I want to share the story below. I began it as one of the narratives for my new book (a rewrite of this, to be published later this year), another of the episodes in the saga of Martha and Mary, those fascinating sisters. But the more I dwelt with that story in Scripture, the more I weighed the words that Martha spoke, then Jesus, then Mary, like gems whose meaning I would check by the measure of their power to burden my thought. I found a theme of resurrection pervading each action, driving each word, and it entered into my mind day and night. What does resurrection look like here, in the broken place? Can we trust God to give it? What does it mean to all of us frail, hopeful little humans bumbling about in the sacred circles of our lives? Perhaps "you will see," (as Jesus said) a few of the same things I found in this story of death turned backwards into life. Happy Easter to you all!

A good Easter Monday to you, my friends. This blessed, rainy day finds Joy and me bundled in my little car Gypsy, rushing down the highway toward Asheville as the sun tussles with yet another storm. We don't mind the rain, in fact, it offers the spice of wildness to our travels. Brooding skies tinge a journey with mystery, while a cup of coffee is good as a faerie's brew to kindle courage in the bones. We have both.

As a last savor of Easter this stormy morn, I want to share the story below. I began it as one of the narratives for my new book (a rewrite of this, to be published later this year), another of the episodes in the saga of Martha and Mary, those fascinating sisters. But the more I dwelt with that story in Scripture, the more I weighed the words that Martha spoke, then Jesus, then Mary, like gems whose meaning I would check by the measure of their power to burden my thought. I found a theme of resurrection pervading each action, driving each word, and it entered into my mind day and night. What does resurrection look like here, in the broken place? Can we trust God to give it? What does it mean to all of us frail, hopeful little humans bumbling about in the sacred circles of our lives? Perhaps "you will see," (as Jesus said) a few of the same things I found in this story of death turned backwards into life. Happy Easter to you all!

Mary & Martha: You Will See The silence after parting from a beloved is a live, insistent presence. Mary hated it; the way the empty air echoes with the laughter of someone just gone. The way quiet seeps in after, slow, like the fall of night. The way you are left not just with yourself, but the staring absence of someone else. Now, Mary tensed as the silence of an irrevocable parting pooled about her. Lazarus, gentle and bright, the young brother whose voice was a music that filled the hearts of his sisters, was dead.

Mary understood why people wept and wailed in the presence of death. To her quiet self, weeping had always seemed too dramatic, but now, she knew. You could only stave off the void of that never-to-be-relieved silence by tears. Alone now in her tiny room, she sobbed. A river of grief flooded her heart and throat and eyes, kept the silence at bay and brought the first comfort she’d touched since four days before when Lazarus died of a sudden fever.

“Stop it.”

As if the sobs had summoned her, Martha appeared, black-swathed and stolid, head high in the doorway. Mary groaned. Her first minutes alone in days, lost. Mourners crammed their little house, clucking, comforting neighbors whose affectionate ministrations were not to be escaped. Mary had thought herself safe. She too would die, she wanted to shout at Martha, if she did not have five minutes of un-peopled space. But the words never leapt, pleading, from her lips. No sound came at all, for how could she speak before the taut, tortured blaze of Martha’s face?

“Mary, we must not cry. Please.”

Mary ceased crying even before Martha strode to her, knelt, and rubbed away the tears in strokes that left red paths down Mary’s skin. Martha’s eyes gleamed black; they stared out like dark gems in the desert of her face where the skin stretched thin, etched deep by the cold of weariness, the heat of grief. Cheeks hollowed, as if by hunger, Martha stared ahead and Mary glimpsed the unspoken pain that devoured the life in her even as they stood together.

“We must be strong,” Martha spoke low again, her voice thick, “we are two lone women now. We cannot fall apart, even now. We must keep our heads and bear this. You must do it with me. Because we are, truly, alone.”

Mary now took Martha’s face in her hands, not flinching at the fever-heat of her sister’s skin, nor the hard aversion of the black eyes. “We’re not alone,” she whispered to her steeled older sister, coaxing forth the tears, the yielding that would heal her of the hard grief. “Our friends will help us,”

“What friends?” Martha whispered, flicking her face in disgust from Mary’s touch, “what can that gossiping bunch and their long-faced husbands do for us now? Everyone we needed has been taken. Father and Mother first, then Jacob, oh Jacob, my husband. And now even Lazarus. He wasn’t much use, but he was a man in the house. And he was gentle, such a sweet boy,” Martha’s voice cracked.

“Shush, Martha, shush. Truly, we are not alone. Jesus…”

Martha shoved herself out of Mary’s grasp and her face went crimson.

“Jesus?” she hissed, “Jesus? He’s not here Mary. Did you notice? He didn’t come. We begged for him to come, to save his own friend, and he, did, not, come.” Martha stepped back, bent double, her arms wrapped round herself as if she were in deathly pain. “Do not say his name to me. Master, we called him. Rabbi. Healer. What of these has he been to us? He neither came nor healed. He abandoned us and he is no longer my master.”

She spat the words and Mary bore their spite, knowing that Martha yearned to strike Jesus and instead could only hurt the one who loved him. Words rose like flames in Martha’s eyes, Mary saw them, but at that moment three wide-eyed women tumbled into the room.

“Mary, Martha,” they clucked, ruffled and restless as hens, “Jesus is here. Jesus is here! He’s coming down the main road and making straight for your house.”

Martha turned, eyes ablaze with fury. White and wordless, she shoved through the group and strode out the door. Chirping with surprise, the women pattered after her. And Mary, arms wrapped round herself, chin hunched into her dark cloak, resting still as a statue in the grey light of the window, was finally left to her peace.

¨¨¨

She could not walk fast enough; she stumbled. She picked up her skirts and her feet and ran. Oh how she hated him. After this she never wanted to see that false face, that cunning kindness again. He had tricked her, left her. Yet still Martha felt that if she could not reach Jesus just now, stand before him with the hard, hot weight of her grief like a coal in her hands to fling in his face, she would die.

Her fury was such that the rumor of it ran before her and the men around Jesus fell back a step. But he did not; he strode forward, steady, so that she met him sooner than she thought and skidded to a halt, panting. She was at no loss; tall, grim, in the dark, rough-woven cloak of her mourning, she drew herself up with eyes that flickered a tiger’s watch of its prey.

“Master,” she spat in greeting, and bobbed her head so that she mocked him with the unbroken glare of her eyes. Every muscle strained, she moved closer, not waiting for him to speak. “If you had been here, my brother would not have died.”

She stopped, choking on her accusation. This was not what she had meant to say. She wanted to scream that he was a liar, a trickster, a wandering poser who ate people’s food and won their hearts and spoke words of hope, then disappeared when pain showed its ugly face. No better than a street magician pulling feathers from people’s ears, while their servants picked people’s pockets. This was what she meant to scream right in his face, in front of those he loved. She could not. Her own heart betrayed her and spoke the truth she could not bear to behold.

He could have saved. He could have healed. He chose not too, and this was the deep, garish hurt. He was no charlatan, no cheap conjurer. The words he had spoken in all those evenings in her home, the kindness he gave her, the life he brought to her family was true as sunlight was true. If he was false, then life itself and the warm earth and the air she breathed must be false, because his goodness was real as the ground on which she stood. She remembered this anew as she watched him bear her words and saw the gentleness, unflinching, the mercy, steady in his eyes. His gaze upon her was a summons. She almost yielded, almost lurched into the arms she know would open, father-like, to catch her.

But she held back, confused. Jesus was the heart that beat life into all creation, how could he allow death? How let his beloved suffer? And die? She knelt abruptly on the pebbled ground, blind and frail in her confusion. No longer could she meet Jesus’ eyes. No one else knew how she had prayed in the dark of those final days as Lazarus lay sweating his life away. A frightened, childlike prayer to God, to Jesus, her faith fragile as a spider’s web yet offered in her darkest hour. Until the last she had hoped. And no answer had come. So now, she would beg. If he wanted dramatic obeisance, she would give it. Yahweh must be closer to the pagan gods than she thought; reluctant to answer until his lovers wrung every drop of tortured self onto the altar. Martha pled.

“Jesus, please. Even now, I know that God will give you whatever you ask.”

She stayed down, kneeling in the rough dust. Pebbles dented her hands; the long brown horizon of the dirt road filled her sight and she could not lift her eyes higher. She felt, more than saw, the feet of a gathering crowd rising like small mountain ranges frozen in place, disciples to the north, villagers to the south. And all of them stared down at her from their sure heights. Martha, the self-assured and strong, was finally humbled. None would join her, she knew, in this brown kneeling valley of loss. None would plead or wait with her. None would stoop to grieve beside her.

But one. She felt the steps as she might an earthquake.

“Martha.” Her eyes flicked up and she was astonished. Jesus was there. The immoveable God knelt next to her in the dirt in front of all the watchers. Jesus sat with her in the echoing valley of her barren, stripped-down soul. Forward she leaned, just barely toward him, lifting her eyes once more to his face, her lips open with shock.

“Martha,” he said again, demanding all her attention now. “Your brother will rise again.”

Again, she almost believed him, almost stumbled childlike into that liquid-eyed love. Then she realized the trick. She closed her eyes and shut him out.

“Yes Lord, I know. In the resurrection. At the last day.”

And small comfort that gave. She wanted life now. Hope, now. Death had defined her for so long. First, a plague had taken the mother and father who were the daylight of her world. Then a field accident had taken Jacob; the burly, blustering, merry-hearted husband who took her in and made a home of laughter for her forlorn siblings. With him, Martha almost believed in joy again. But after she buried Jacob, she gathered her brother and sister into the strong, beautiful home her husband had made them, and for a month Martha did not leave her house.

When she finally emerged, she was hard and bright. She ruled with the tenacity of death itself. No longer would she cry like Mary. The luxury of a tender heart had passed her by. She died to joy so that she could protect the ones she loved. She ruled, steel-bright, over her laughing brother and gentle sister. She sheltered frail Lazarus, she bossed the grieving Mary and made a household that seemed a small fortress against poverty or illness. Now again, death tricked her and stole the very thing she had given her soul to protect.

Through it all, through every death, God but watched. Never had he saved or stayed the iron fist of loss as it crushed her. Now, God stared out at her through the gentle eyes of the man who called himself son to the Almighty. And this God demanded that she believe in life. “Lazarus will live again,” he said. This Messiah asked her to believe that he had not betrayed her.

“I am the resurrection. I am the life,” he spoke now with a vehemence that drew her from her introspection, his face flushed with the truth of the words. He grabbed both her hands and caught her eyes. Life knelt before her, kind and fierce, his eyes a fire upon her face. “Anyone who believes in me will live, even if his body dies. And Martha, everyone who believes in me, who lives in me, will never die. Never. Do you believe this?”

His question was spoken so quietly, the nearby crowd did not hear. But Martha did, and knew that her answer would define her life. The pain of her doubt creased her face, and she rocked, aching, trying to form an answer. Lazarus was dead, her husband was dead, and grief was a pit in her soul. How could she believe the promise of Jesus?

But how could she not? Stripped now of every prop that ever staid her faith, bereft of her brother, kneeling in the dirt, Martha looked straight back at Jesus. And she knew. Either life beyond the hands of death, hope beyond all the grief of the world, and infinite love were true, or they were not. She could not dabble in doubt and think it would not kill her. Faith was not a toy she could pick up when she liked, then set it down. One truth must be chosen, and she must fling herself body and soul into the choice. Choose doubt? Choose to believe that death was the end of all things, that love would be crushed, that hope was a fancy for children? No.

Only one choice remained. She must trust in a life and power beyond her sight. She must fling a cry of faith into the very face of death, stare him down and declare him somehow beaten, because this was the only answer. If Jesus was true, then his life must be true, even when she was blinded by loss. Life must be working to turn back death even now. The choice was made, and she opened her hands, yielding her spirit to the master who knelt before her as a strong, strangled cry broke from her throat.

“Yes, yes, I believe.”

The crowd stirred around her, and Martha scrambled suddenly to her feet, eyes brilliant with the words that burgeoned suddenly to life in her, like the gathering of light at dawn. Her old self settled back on her shoulders and she stood straight, placed her hands on her hips, took a deep breath and spoke exactly what she must, “yes,” she declared, her voice strong and golden, “I believe. You are the Christ, the son of the living God. Yes, I believe.”

And then she was weeping as grief and faith rushed together within her and made a flood of joy unlike anything she had ever felt. Jesus opened his arms, and she fell into them. This was her truth. From this moment forth she would walk in the love of this gentle God. Though death strike her heart and fear her soul, yet she would be safe, held in the firm hands of this God whose robe was dusty from kneeling with her, whose hands were striped by her tears. She was sure now, as Mary was sure of this one good thing, of a love beyond any sorrow, and better than any joy. Yes, she believed.

¨¨¨

“Mary, Mary! Where are you?” the vibrancy of the voice startled Mary from her thoughts in the corner. The cry was Martha’s, she knew, yet she questioned her senses. This was Martha’s voice changed; some weight had been lifted, some shadow blazed away from her tones. It was, Mary knew with a thrill, the voice of Martha’s girlhood, the voice that sang music from stone to rafter in the early days before the world was broken.

“I’m here Martha, here,” she called, stepping into the next room where a warm, black-swathed hurricane threw itself around her. Martha was hugging her. This took Mary a few seconds to digest, and it was with shocked, shaking hands that she reached her arms round the moist bundle of womanhood that trembled before her. Wet, yes, for Martha was drenched in tears. They slicked her face and soaked her scarf. But as Mary pulled gently back, it was Martha’s eyes she feasted upon; eyes clean and cooled, grey eyes with light springing up like water from some deep well. She saw a face with the curved softness of a child’s, the anguished lines filled in with love, the hard red anger washed away. Seeing it, Mary began to weep and this time Martha did not stop her. They clung together, faces hidden in each other as their broken world was cleansed. Finally Martha whispered, “The Master wants to see you.”

Mary rushed from the house. A bevy of women followed, but she didn’t see. Swift in her love as Martha had been in her anger, Mary ran up the road to Jesus. No hesitation stayed her feet. No anger restrained her. She fled swiftly to the heart that had already cradled her soul for the past four days. Straight to the arms that would shelter her through every darkness and turn every death back to life.

The villagers made a circle around her just as they had with Martha. Before, it had been a ring of curiosity, now they lined the space where Mary wept and there was a gentle longing in their faces. Mary knelt at Jesus’ feet and he knelt to meet her, to hold her as she shook with grief and finally, repeated her sister; “if you had been here, my brother would not have died.” With her though, it was assent. He could have saved, he did not. She trusted his love. And yet that love was already turning death to life.

Mary lifted her face to Jesus, and hope glimmered in the black of her eyes like the first hint of dawn. Martha was healed. Martha who had been dead in soul sure as Lazarus was in body. Life was already turning death backwards so she would cling and weep at the heart of it and… watch. There was a light mixed with the grief in Jesus’ eyes as he watched her face.

“Take me to the tomb,” he said. At once, there was a mass of feet moving and elbows nudging as the crowd pressed close to Jesus.

“This way Rabbi,” said gruff, wizened men and squirming children alike, careless of anything but his favor. They reached the place, just beyond the edge of the village, a cave fashioned into a handsome tomb. Back they drew then as they had with Mary, and made a circle around the entrance of the tomb. The first circle had been of love, a sacred place. This too was holy, but it was the circle of death, and no one wanted to draw too near it. So Jesus stepped in, alone. He walked forward, put his hand on the stone that sealed his friend away from the faces that loved him. He bent his head, and he wept.

Martha watched and marveled that God himself should stand at the site of her loss and share her grief. Mary watched and ached to see Love bear her sorrow, love stand at the place of broken hearts and somehow begin the turning back of death. The crowd watched with faces softened, eyes, even the old ones, misty with tears. Here was a Rabbi who did not stand apart from their grief, spouting platitudes and proverbs from the Torah while widows and children wept. This was a teacher to grieve alongside them, honor their pain and make it his own.

A few crusty ones, crusty not in face or bones, but soul, stood aside and whispered that this was a mockery since a healer of blind men ought to have saved his friend. But they were unceremoniously jabbed in the ribs and shushed by their neighbors, who said you could not doubt a rabbi willing to weep. The whole crowded circle leaned forward toward the brave, weeping man. Suddenly, he straightened, struck the tombstone with his fist and turned.

“Take away this stone.”

Silence, frozen, met him. Eyes wide and whitened as sea stones stared at him all around. He smiled, strode over and smacked a few of his friends on the shoulders. “Come, quickly, help me. Move the stone.”

His words gathered vim and volume, brightness glimmered in his eyes as five men heaved and hacked at the stone.

“Lord,” it was Martha, squirming, her hands twisting, her face blotchily flushed. “He’s been dead for four days. He’ll stink.”

Jesus, Mary swore afterwards, rolled his eyes and laughed, but Martha never saw it; she was too busy cringing and wishing these practical observations could be kept from her lips. Jesus stomped over and stood right in front of her.

“Martha.” Jesus was grinning. “Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?”

The stone was gone. A black, dusty hole gaped in the mountain wall, dust motes fled from it into the grey light. Jesus turned to the shadow and planted himself dead center, face uplifted, arms outstretched, fronting the blackness.

“Father,” he cried so that everyone there was arrested by his voice, “I thank you that you have always heard me. I know You always do, but I say this aloud today for these people here, so that they may know that You have sent me.”

The last words struck at the darkness and stone like a hammer; they rung from rock to rock, hard and brilliant, chipping away at death and fear.

“Lazarus!” Jesus’ voice was an earthquake, a whirlwind, a roar of thunder at highest storm, “come forth!”

In a symphony of echoes, the command rose up and shook the air. In an instant, the crowd heard a scrabbling inside the tomb, the pat and swish of feet in the rocky dust, the plink of stones kicked out from moving feet. Jesus’ cry still echoed round as a slight, linen-swathed figure stumbled into the cave’s dark entrance.

The crowd stood like dead men, watching. Not a muscle twitched among them, breaths were barely drawn as Jesus stepped up and unwound the slender, white strips of cloth from the figure’s face. First came eyes like the brown earth washed in sunlight and newly turned in spring. They glittered with life. Then, inch-by-inch, the face, firm with joy, until the lips were free and Lazarus met the eyes of his Lord.

“Jesus,” he said, tears in his laughing eyes, an imp’s grin on his boyish mouth, “you called?”

And the silence of the tomb was shattered in a cacophony of laughter. Wild echoes of joy leapt and cried as the crowd roared to life. People danced and laughed, grabbed each other by the arm and spun each other round. Mary tumbled forward and grabbed her brother. Martha could not decide whether to sob or laugh and so choked herself merrily on both as she clutched at Lazarus’ free arm and met the life in his eyes.

“Martha,” he blurted, “good grief, you’ve been crying. You’d think I’d died or something.”

And then she laughed indeed, bent double with a joy that broke and healed her all at once. She laughed as people wrung her hands in congratulations, as Mary jumped up and down. She laughed as the circle of death filled with dancing because Love had come among them and Love had not failed. She laughed as her eyes were filled with the sight of the glory of God.

Read Part 1 here.

Tonight, he would visit their home. He came often these days, for Lazarus loved him as a brother and honored him as a king. Mary lit up like the sun at the very mention of his name. Even Martha, won by his admiration of her cooking, was glad to admit him into her home and host the meals and debates that soon became the talk of the town. Tonight’s feast had been three days in the making. The fame of young Jesus spread far and wide, and Martha was sure that the wisest of the town would show up at their door the moment the Rabbi stepped in.

Read Part 1 here.

Tonight, he would visit their home. He came often these days, for Lazarus loved him as a brother and honored him as a king. Mary lit up like the sun at the very mention of his name. Even Martha, won by his admiration of her cooking, was glad to admit him into her home and host the meals and debates that soon became the talk of the town. Tonight’s feast had been three days in the making. The fame of young Jesus spread far and wide, and Martha was sure that the wisest of the town would show up at their door the moment the Rabbi stepped in.

Mary’s foray to the market was the last of many. She rummaged in her basket; onions, a few herbs, one more bunch of garlic. All was in place. Her feet beat a quick tattoo on the homeward road. Martha was in more than a usually fierce state of mind; hospitality often had this effect on her, however much she protested her love for it. She would not look kindly on dawdling. Mary turned the last street and could almost see her house when a scratchy voice called to her from a nearby door.

“Mary, Mary!”

There stood Anna, a woman so bent and hollowed by age, she was like a husk of grain when the meat is gone. Wrinkles cobwebbed her face, her voice was an echo from her youth that rattled in her throat, and all that was left to brighten her was the sharp, eager light of her eyes. She beckoned now to Mary, her face in a forlorn smile.

“Please little Mary, for I remember you so, when you were a child. Be a dear and reach a pitcher for me. I’m so bent now, and maybe you could tell me what’s going on to make your rush up and down the street these last days?”

Mary almost walked on. Anna was notoriously talkative and Jesus was due to arrive by sundown. Yet just as she stepped away, turning to fling a protest that she must hurry on, a catch came strongly to her heart. Look, said her heart, look at the woman before you leave.

So she turned her eyes to Anna’s face. The hunger there was plain. She looked longer and saw the frailty of a widow who could no longer fend for herself. She saw loneliness, the yearning of a talkative woman relegated to the edges of all things by age and a weakened body. And she knew she must enter, even if for a moment, to whisper every detail of the feast. She must tell Anna all she knew of Jesus, must fetch whatever jug, or joy, was beyond the woman’s reach. Her lingering would be love, for she would see Anna in just the way that Jesus had noticed her.

In the weeks since her meeting of the Jesus, Mary had pondered what it meant to live out the love he gave her. He spoke of God loving his people, of his kingdom come and of those who brought it crashing into the present by the love they gave. What, she asked, did this mean she must do? She knew now, abruptly, with Anna’s creased face before her, that love is a flow back and forth from the heart of God to his beloved, and out, ever out, again. To be seen, and then, to see.

Martha would just have to wait. She stepped up to the door...

Martha beat the batter as if it were Mary. She glared into her bowl and smacked it on the wooden table and growled under her breath. Left alone, again. Left to cook and tend, to fetch the water and greet the guests. Left by a sister who was forever happy these days, while Martha herself felt only harried. No one, she thought and gave the batter a last, devastating stroke, knew the amount of work her life demanded. They all seemed to think food fell hot from the sky. She held up her household and fed multitudes and they all, siblings and honored guests alike, pranced about enjoying her work and never did anyone think what it cost Martha. No one ever saw.

Mary ducked in the door. Martha shot her a daggered glance and shoved a bowl into her hands.

“What took you so long?”

“I’m sorry Martha, Anna needed help.”

“Old Anna? Oh, I can just see the two of you gossiping the day away. You are always with your head in the clouds while I have to work down in the real world. I despair of you Mary. Now hurry up, chop these onions. The Master and all those men arrived while you were out and they are sitting upstairs waiting for their dinner.”

“He’s here?”

Mary’s face was like the sun in the morning and it maddened Martha. Like a lovelorn girl she was when Jesus was near. Martha rolled her eyes and did not deign to answer.

“Martha, if we finish quickly, we can go listen to him. You must join us tonight, hear all that he says. He loves it when we come.”

Martha whirled about, marched to where Mary sat with her work and glared down at her.

“Mary, the master doesn’t care that we listen as long as we cook. You act as if he is personally concerned with your presence. He’s not. No, no argument. I’m going to fetch water, since you apparently forgot. See if you can get the main dishes on the table without me. That would be a miracle worthy of Jesus himself.”

And refusing to see the hurt that kindled in Mary’s eyes, Martha marched from the house and into the night. The chill of the air cooled her a bit and by the time she reached the well, the patter of her heart and brain had slowed. She sat on the stones that rimmed the well and was aware, abruptly, of how her bones begged her to sit, how her muscles protested at thought of heaving that jar back home. She settled in.

Let Mary shoulder the work for a spell. Let her feel the burden Martha felt every day – maybe, Martha grimaced to herself, it would force her to thanks. The hush of a wide-open, starlit sky covered Martha and in a rare stillness, she looked up; she even marveled. How beautiful. She should do this more often. Mary was always gaping at stars and sunsets; perhaps there was something to it after all. Perhaps there was something to Mary’s idea that Jesus hoped for her presence too.

Here, Martha wrinkled her nose. Mary was wrong about that. No Rabbi ever asked her to sit and listen; only men, and the richest of women were offered that grace. Besides, the ways of the town were set. Men listened, women worked. The ways of Martha’s mind were set; she cooked, Mary dreamed. The world ran on in its demanding way and her lot was to meet it with head flung high. Jesus didn’t want her to lounge at his feet and listen; he wanted a hot meal and that on time.

Time to get back. Mary would, of course, have floundered. The pull of work stood Martha straight and prodded her into the homeward march. She stepped into the house, all ready for Mary to rush up in a tizzy. But all was silent. The food seemed all to be upstairs; Mary had managed at least that. All seemed even to be in order, the vegetables covered, and the cooking tools put away. But Mary was gone. Martha crept a few steps up toward the room and… there. She knew it. Mary sat rapt at Jesus’ feet, no longer aware of Martha or meals. Fury rushed in a flood through Martha’s soul, filling her mouth, her heart, her eyes. She stomped up the last steps...

Mary felt the heat of Martha’s anger like an open oven door on the back of her head. The silence came first, as tongues stilled and faces turned, curious, to Martha’s hands-on-hips presence. Even Jesus hushed and Mary didn’t wonder, for the blaze of Martha’s eyes and her out-flung hands demanded attentive silence. Mary cringed.

“Master,” Martha barked, hoarse-voiced with fury, “do you not care that my sister has left me to do all the work? Then tell her to help me!”

The men raised their eyebrows, Peter whistled low, and Mary kept her crimson face down as she rose to go. Then, “Martha…. Martha….”

The voice of Jesus was like a mother wheedling a stubborn child. It was the voice of a father who knows the childish fury of the little one he holds and plans to take her upset away. His voice was a plea, an invitation, a tender command to be still.

“You are worried and distracted about many things. But Martha, there is only one thing needed. Mary has chosen the better part, and it won’t be taken away from her.”

Martha opened and closed her mouth like a fish out of water, gasping and gaping at the gentle rebuke. Then she fled.

Mary rose then, her face no longer crimson. She glanced at Jesus, caught the slight nod of his head, and followed her sister. She left her place at Jesus’ feet, not for shame or guilt, but in search of a sister who needed finding. Healed of a long blindness, Mary saw in sudden clarity that Martha felt lost as she once had. The noise and bluster of Martha hid an aching heart, even as silence had veiled Mary’s. The anger of Martha was a cry for someone to see a heart that languished, a soul weary with work. Mary had been found and seen. Now Martha must as well.

She found her sister crouched on a low stone wall in the alley behind their house. Neither spoke. Mary settled beside Martha and for a time, they were quiet in the dark. Then Martha sighed deeply into the night.

“Well Mary, you were right. He did want you up there. Though I’m pretty sure you are wrong about him wanting me.”

“Martha. He sent me to find you.”

“What?” Mary could feel Martha’s skeptical gaze upon her even in the dark. “Why? I accused him. I accused the Rabbi. Why would he want me there?”

“Because he wants the same joy for you as for the others, as for me.” “Oh yes, that’s right,” said Martha wryly, “you chose this “one good thing.” And what is that?”

“Just to be with him. To hear all he says, to learn about love. You know Martha, he really is everything he says. He is the Messiah. And the Messiah is for all people. I think he wants you in there even more than he wants another feast – though he does enjoy those I’ve noticed.”

Martha laughed and Mary grinned in triumph. She settled closer to Martha on the night-cooled stones, the air dry and starlit around them.

“Martha,” said Mary, and put a tentative hand over her sister’s, “you have always been the strong one. I know you have had to work to care for us. You have always been the queen, always the best of our family.”

To her eternal shock, Mary caught the sound of a sob and from the darkness, Martha spoke, choking on her words.

“No one ever seems to notice. You and Lazarus, always laughing together while I work apart. You with Jesus, like a girl in love. But I can’t be gentle and yielding like you. I’m not quiet. I don’t know how to be anything else. But no one sees my heart. I’m not so strong as you think.”

“Oh my Martha, Martha! You must rest,” and Mary reached a hand to Martha’s, “you must let Jesus love you. I’ll take care of everything; I’ll make all the meals and clean the house, just come and sit with Jesus for awhile. I know he’s waiting for us.”

Mary risked a side-glance and saw Martha’s lips pursed and her eyes glaring straight ahead.

“They’ll laugh at me. All those men. Especially that Peter.”

Mary herself laughed then, and threw her arms around the stubborn Martha.

“If they laugh,” she declared with unwonted ferocity, “I’ll send the lot of them out the door. And Jesus will help, I’m sure. Come on Martha. I’m the eldest tonight. You’re coming with me.”

With an arm through Martha’s, Mary rose, pulled her sister to standing and marched the both of them straight down the road and into their house. Up the stairs she pulled her lead-footed sister until they stood once more in the long, low room. The spice of Martha’s feast still scented the air, people hunched in small groups, abuzz with discussion, the shadows were warm and filled with murmurs, and at the far end sat Jesus. He raised his eyes to Martha’s the instant they entered. Lazarus too looked up, saw the way Mary tugged Martha along, and instantly moved aside so that a place sat open at Jesus’ feet. Peter, then Judas, threw arched-eyebrow glances Martha’s way, but Mary glared at them both with such rare furor, they cowed and dropped their gaze. And now, Mary knelt on the ground and Martha stood, like a small, troubled girl, her hands and face in a twist of pleading. She lifted her face to Jesus. He grinned.

“Martha,” his eyes saw her very soul, “I’ve been waiting for you to come.”

I am reading Irish Fairy Tales, the old version by James Stephens, illustrated by Arthur Rackham. And in amidst the fantastical tales, oh-so-artfully spun, are these wise little asides, these tiny bits of philosophy that set me in a ponder all the day. Here. Now you can ponder too:

We get wise by asking questions, and even if these are not answered we get wise for a well-packed question carries its answer on its back as a snail carries its shell. Fionn asked every question he could think of, and his master, who was a poet, and so an honourable man, answered them all, not to the limit of his patience, for it was limitless, but to the limit of his ability.

"Why do you live on the bank of a river?" was one of the questions.

"Because a poem is a revelation, and it is by the brink of running water that poetry is revealed to the mind."

"Have you caught good poems?" Fionn asked him.

"The poems I am fit for," said the mild master. "No person can get more than that, for a man's readiness is his limit."

Today I bring you... a peek into the new book! The basic gist of the thing is that I wanted to tell the stories of women who were heroines in the Bible. But I also wanted to give the truth "scope" as one writer character so neatly put it. Sometimes I think we idealize women like Mary or Esther to the point of impossible sainthood, when they were really just workaday women with hopes and hurts and long-hidden dreams. The miracle was that they offered the whole of their hearts to the living God, and he is always waiting for just that to begin a grand old story in any girl's life. So, tell me what you think (the editing is ongoing!) and enjoy the first bit...

Her name was Mary.Martha's sister some called her, but she didn't mind so much. At least not now. For many years the name was a thorn that grew near her heart and pricked each time she heard it. Mary was of the dreamer's race, a hushed woman whose inner vim gleamed only in her eyes. Words came slow to her lips, but gentleness swift to her hands. The children knew Mary, and came always away from Martha's hushed sister with brighter faces. At those times, she spun through the house with "her head in the clouds," as Martha was known to say. Yet few stopped long enough to see the soul that looked out of her face. None saw the hungers and pent up loves that pooled so silently in her eyes.

Martha was the one that everyone saw. Martha, whose whirlwind drew all she encountered into her ever-quickening spin. Martha - the bright and opinionated, Martha, the friendly and amusing. Martha whose plans spun a web of minutes that captured Mary's days. Mary never refused the help or time Martha assumed was offered. But sometimes when she walked in twilight to the well, heard those words, "Martha's sister,” as if she, Mary, had no name, no soul to be known and loved, she felt like a ghost. As time marched on, she wondered if any would ever know her heart.

Until the sunny market day when one pair of eyes set themselves upon her and she was seen. Not simply looked upon, but known. There was no other word for that one man's gaze upon her, the gentle insistence of his eyes, as they held her own and found the secrets she hid within them. He had seen her even amidst a crowd, singled her out with his care, and the love she bore him was absolute.

Down to the market the sisters had gone on that sharp spring morning, Martha's step like a soldier’s march, her cloak in commanding swirl. Merchants cringed at sight of Martha; her skill in the art of the bargain was legendary, and she forayed into the fray of vegetables, fruit, and raised voices with relish. Mary walked always a little behind with the basket. The sun rose hot and swift that day, and when they reached the final stall on their rounds, Mary sighed. The war of the flowers, as she secretly named it, was nigh. Martha insisted that no handful of field lilies ought to cost more than copper, while the flower-woman, Ruth, insisted they were worth at least three. Wits and words were flung to astonishing lengths in this weekly fight, so Mary set the basket down and stretched the stiffness out of her back.

She glanced up the street; the narrow, dirt alley whirred with market-day color. At the farthest end, she glimpsed the cool, blue corners near the synagogue. Damp, and strangely sweet the air down there; she glanced again with longing eyes. Martha was deep in the heat of her battle now. Mary backed a step away and took one step, another; she would be back before Martha knew she was gone.

She walked slowly at first, running her fingers along the cool silks and scratchy weaves in admiration, her eyes hungry and glad for the hues of mounded fruits and bunched flowers. Alone now, she remembered to glance up, her timid eyes catching the eager gaze of the merchants with their quick, broad smiles. One old woman caught her shy smile and pressed a flower into her hand. Mary could not help a small grin as she ambled on.

Finally, she reached the shadows. Their hush fell over her flushed face and robed her in their cool as she leaned against the stones of the synagogue. How good to be still, enveloped in calm. Gradually, she heard the buzz on the other side of the stones and her curiosity drove her to creep up near the entrance and set her ear to the shadows inside. She loved to listen to the Rabbi discuss the Torah with his disciples, loved the mystery that lingered in the words of the prophets. These were the words of the God who had made her. At those times she felt that perhaps he saw her, even if no one else did.

But today, the clamor inside chased away the usual hush. A feverish tone heightened the voices of the young men, while conversations buzzed low in countless whispers among the men huddled in small groups outside the synagogue door. And through it all thrummed a single voice, low, rich, sometimes calm, sometimes eager. The whispers burst out anew after every word. She did not recognize the voice and hovered nearer, hoping to catch few words.

"No, no, you have it wrong," she heard the voice exclaim, "the law is not God. God is love, and he has so loved his people that he has sent his son to do what the law cannot; save you from your sin. The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is the God of Love."

The sharp breath escaped her before she could stop it. God as the love for which all people longed? The thought of it stirred her lonely heart, stirred the quiet depths of yearning she hid in her silence and she could not turn away. The group was breaking up for the midday meal, the young men and rabbis pouring out of the shadows into the light of noon. Mary pulled back and drew her shawl close as they passed her. But she would not move or return to her proper place with Martha and the village women until she had seen the owner of that voice. The voice that said God was love... she flinched as her brother came out the door and saw her.

Lazarus stared for an instant, his lean, young face confused. He frowned; it wasn't proper for Mary to lurk around doors like that. Why did his gentle sister linger among the men? His eyes shot puzzled, if gentle, irritation at his usually docile sister. As men poured out of the synagogue, he nodded toward the market, where Martha's sturdy figure was plainly visible. Mary shook her head and averted her eyes as the last of the crowd came out. Lazarus stepped forward, but then, there he was.

She knew him immediately. Only that face, firm, yet lined with compassion, only those eyes, brown and friendly, could have owned the gentle voice. She stared, unaware of the others, unable to move. He was talking with a young man whose eyes blazed with argument, but he said a final word, put a hand of peace of the man’s shoulder and turned. In that instant he found her eyes as if he had been expecting to see only her, and they were filled with something that puzzled and gladdened her heart: welcome.

"Ah Rabbi," said Lazarus, plainly miffed at Mary's boldness and feeling pressed to explain her presence, "this is my sister,"

"Mary."

The teacher spoke her name in harmony with Lazarus, but she only heard the rabbi's voice. For he saw her. He knew her. Not just her name, but all of her. In the split second instant of his glance she knew that he saw everything: the un-given love she hoarded within her, the ache she felt at being forgotten. He saw the deep hush of her need, and yet saw too the strength, the beauty that dwelt in her quiet. He saw the music that danced in her thought, and the love she bore the children. He saw and knew and somehow, healed. For an instant, the whirl of the sun was halted. And when it began again, she was known and would never be forgotten again.

"Master," she said, forgetting her quiet, the single word laden with her joy. "I have always wanted to meet you."

"Then come," he said, to the half-scandalized eyes of the men around him, "follow me. After all, we are going to your home." She had. Ignoring the eyes of her brother and the men that clamored round him. She pushed back Martha's glare as she rushed up, astonished, her cloak in a billow behind her, lilies clutched to her heart in triumph. Up the streets, up all the old ways of her life, she followed this man, her master into the cool of her own home. He shared their meal and sat at the table, talking the whole afternoon and into the night. She listened. And knew. And loved beyond what she had ever thought she could.

And now she was Mary. Sweet yes, and still quiet. Still Martha's sister. But a changed Mary nonetheless who walked the evening street with an easy gait that caught the smiles of the last market women and glances of the young merchants as they packed their wares and headed home. She was loved, known, the heart of her held and it changed the very way she looked upon the world about her. A month had passed since that day in the market when she had met the rabbi Jesus...

To be continued...

College thoughts and my usual bent toward words have set me in a world of poetry lately. I consider myself an amateur in knowledge of the genre, though an expert by way of the love I bear it. I've read poetry since a child, poring over old collections or dusty old volumes I picked up at book sales. I've even memorized a good few, inspired by the Anne of Green Gables characters who could spout reams of poetry at the least provocation.

But lately I've gone a little deeper. To start with, I'm reading Beowulf, the oldest surviving poem in the English language. I started by reading Seamus Heaney's introduction to his particular translation, and was awed by the structure with which Anglo Saxon poetry is written. The careful selection of words, the bendable, but definite form required for epic poetry, it is an art to which I had given little thought. I've also been reading Shakespeare aloud (with an English accent, mind you!), attentive to the cadence of iambic pentameter, the way the words not only mean something on their own, but combine in rhythm to create a deeper song.

College thoughts and my usual bent toward words have set me in a world of poetry lately. I consider myself an amateur in knowledge of the genre, though an expert by way of the love I bear it. I've read poetry since a child, poring over old collections or dusty old volumes I picked up at book sales. I've even memorized a good few, inspired by the Anne of Green Gables characters who could spout reams of poetry at the least provocation.

But lately I've gone a little deeper. To start with, I'm reading Beowulf, the oldest surviving poem in the English language. I started by reading Seamus Heaney's introduction to his particular translation, and was awed by the structure with which Anglo Saxon poetry is written. The careful selection of words, the bendable, but definite form required for epic poetry, it is an art to which I had given little thought. I've also been reading Shakespeare aloud (with an English accent, mind you!), attentive to the cadence of iambic pentameter, the way the words not only mean something on their own, but combine in rhythm to create a deeper song.

What is the use of form? In our free verse, free love, do-what-you-want world, the idea of restricting our thoughts to any stricture of form or cadence can seem like a curbing of self. Or is it, instead, an enrichment? A restraint that gives more power to the words we choose, a careful pruning of what is unnecessary, so that the full weight of an idea may shimmer in the form of a single poem? I found this quote from Tobias Wolff's novel Old School, to help in my ruminations:

I lost my nearest friend in the one they call the Great War. So did Achilles lose his friend in war, and Homer did no injustice to his grief by writing about it in dactylic hexameters... But about my friend, I wrote a poem for him. I still write poems for him. Would you honor your own friends by putting words down anyhow, just as them came to you - with no thought for the sound they make, the meaning of their sound, the sound of their meaning? Would that give a true account of the loss?... I am thinking of Achilles grief, he said. That famous, terrible grief. Let me tell you boys something. Such grief can only be told in form. Maybe it only really exists in form. Form is everything, without it you've got nothing but a stub-toed cry, sincere maybe, for what its worth, but with no depth or carry. No echo. You may have a grievance, but you do not have grief, and grievances are for petitions, not poetry.

I'm just beginning to really consider it all. What do you think?

(And if you haven't already, and want lots of poetry to think about, like me, sign up at Davey's Daily Poetry, as I've mentioned before.)