Dreamers and Keepers

St. Brendan was a seafarer. Why? Cloistered, devout, he was but a young monk alive in a world still haunted by the furies of old pagan gods, hemmed in by the pathless sea. Danger abounded in brigands and storms and petulant kings. Yet an old monk mumbled a half-baked dream, murmured of paradise gained, and off sailed Brendan over the wild waters, in resolute search of Eden.

St. Brendan was a seafarer. Why? Cloistered, devout, he was but a young monk alive in a world still haunted by the furies of old pagan gods, hemmed in by the pathless sea. Danger abounded in brigands and storms and petulant kings. Yet an old monk mumbled a half-baked dream, murmured of paradise gained, and off sailed Brendan over the wild waters, in resolute search of Eden.

Jane Austen was an observer. Why? With a knife-keen wit and a mind to unsettle the wisest, she could have striven to philosophical heights. Instead, she spied on her neighbors, and wove the quips and foibles of dining room drama into immortal tales. Brilliant woman, parson’s child, country-bound spinster aunt, she questioned not her lot, but found it to be a merry drama and was glad.

Jane Austen was an observer. Why? With a knife-keen wit and a mind to unsettle the wisest, she could have striven to philosophical heights. Instead, she spied on her neighbors, and wove the quips and foibles of dining room drama into immortal tales. Brilliant woman, parson’s child, country-bound spinster aunt, she questioned not her lot, but found it to be a merry drama and was glad.

Galileo was a doubter. Why? Taught to believe that the earth was settled perfectly in space, the glorious center of everything, he balked. Believe without question? Not him. He studied and stargazed and flung planets from their thrones with never a second thought. One peek through a telescope, one hunch in a prickle up his spine, and off he ran to prove what had never been seen.

To me, the people of earth are divided by lines of desire. Dreamers stand on one hand, and keepers sit on the other. Restive and restless-eyed souls are the dreamers. They are the hungry-hearted, with wanderlust thrumming in their blood and eager brains, ever in search of what lies a fingertip just out of reach. Truth or beauty, treasure or friend, they would risk their life to find the unseen ideal. In the annals of time, the dreamers play out like high, bright notes in a symphony. St. Brendan had to find heaven if it could be found on earth. The call of it just beyond him was a song he could not resist. Galileo felt that all was not as he had been told. Never could he rest until he searched out the truth he sensed in the deepest parts of himself. So it is with all dreamers. They are the explorers, the artists, the sailors, and searchers who ever beat down the walls of the known, intent upon finding what has never been found.

To me, the people of earth are divided by lines of desire. Dreamers stand on one hand, and keepers sit on the other. Restive and restless-eyed souls are the dreamers. They are the hungry-hearted, with wanderlust thrumming in their blood and eager brains, ever in search of what lies a fingertip just out of reach. Truth or beauty, treasure or friend, they would risk their life to find the unseen ideal. In the annals of time, the dreamers play out like high, bright notes in a symphony. St. Brendan had to find heaven if it could be found on earth. The call of it just beyond him was a song he could not resist. Galileo felt that all was not as he had been told. Never could he rest until he searched out the truth he sensed in the deepest parts of himself. So it is with all dreamers. They are the explorers, the artists, the sailors, and searchers who ever beat down the walls of the known, intent upon finding what has never been found.

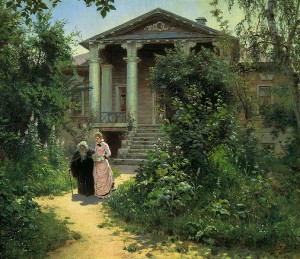

The keepers wait to welcome them home. They are the glad-eyed and frank-faced souls, who settle and stay with a faithful joy. The song of the unseen troubles them not; they feel instead the dance of the seasons, the cadence of days as time sings in the here and now. The present reaches a powerful hand from the deep earth and roots them, happy, to their one place in the wide world. They craft and build, they keep what is civil and lovely alive, they master the art of life lived richly. In the symphony of time, they are the rich-throated hum of low violins, the myriad voices who weave the steady, marching song of the earth. Keepers are the good kings who set their hearts to cultivation instead of conquest, the Jane Austens who revel in the merriment of every day. They are the rulers and builders, the farmers and reapers of harvests, the faithful who keep all that is good in place throughout the ages.

The keepers wait to welcome them home. They are the glad-eyed and frank-faced souls, who settle and stay with a faithful joy. The song of the unseen troubles them not; they feel instead the dance of the seasons, the cadence of days as time sings in the here and now. The present reaches a powerful hand from the deep earth and roots them, happy, to their one place in the wide world. They craft and build, they keep what is civil and lovely alive, they master the art of life lived richly. In the symphony of time, they are the rich-throated hum of low violins, the myriad voices who weave the steady, marching song of the earth. Keepers are the good kings who set their hearts to cultivation instead of conquest, the Jane Austens who revel in the merriment of every day. They are the rulers and builders, the farmers and reapers of harvests, the faithful who keep all that is good in place throughout the ages.

We are born, every one, to be a dreamer, or a keeper, and in some, perhaps there is a little of both. But no matter which, we must push the song of our soul to its full beauty. The world needs the good that both bring. Evil is defeated by the dreamers whose souls rise to cry against all that is wrong, and the keepers already deep in the daily, gritty work of pushing back the dark. Beauty is cultivated by the keepers who shore up the world with civility, even as dreamers sail back and forth in search of newer, unknown good. Together, they weave the music of their souls, their work, and their wonder into a joyous symphony of fellowship. And this is the song the whole world was made to sing.

(Inspired by yet another admissions essay prompt: what are the two kinds of people in the world?)